Progress and Phenomenology: Value Is Vitality

August 29, 2022

Something is awry in the relationship between progress and phenomenology. Progress is becoming a technological quest, searching for greater longevity, increased productivity, and wider frontiers. But along the way, we’ve lost critical, complementary focus on what these new, technologically augmented ways of living feel like. We’re designing a world irrespective of the phenomenologies it fosters. Is life, as an experience, growing increasingly worth living? Is it growing richer not only in material terms, but experiential terms?

I call this the The Pessoa Problem. The poet Fernando Pessoa once wrote that life “all comes down to trying to experience tedium in a way that does not hurt.” Now, Pessoa wasn’t a cheery guy, and we shouldn’t read him as representative of today's majority mood. But I do think that his line can be read as a warning. A harbinger of where, without careful recalibration, we may be heading. The Pessoa Problem is both a critique of, and concern for, the trajectory of modern phenomenology.

Good artists are usually ahead of wider cultural phenomena. The Pessoa Problem gestures towards a quiet crisis surging just out of sight. Left unaddressed, it may not crash upon us and wipe us out, but worse. It may leave us as a society of Pessoas1. Alive, but merely enduring. Existing, but vacantly. Instead of ebullience at the marvel of being alive, there would merely be the tedium life entails. This is not progress.

I’ve tried thinking about this problem from numerous directions, all of which wind up feeling partial, and ultimately insufficient. Philosophy of mind, cognitive science, psychology, and literature are all helpful in elaborating the problem, but short on solutions that can reach beyond individual responsibility. Economics, critical theory, systems theory, even ‘progress studies’ offer scalable courses of action, but lack a normative foundation to guide them. But finally, It feels like I’ve found an approach, a tradition, that with some tweaking, can both square us up to the problem, and orient us towards an appropriate response.

What I have in mind is “value theory”. And if you’ve never heard of it, that’s sort of the point. Once a centerpiece of sociopolitical discourse, today, value theory is nowhere to be found, and we’re paying the price.

In its simplest terms, value theory asks what value is, and how we might cultivate more of it. Or, as one group of academics put it, value theory “is about how, [in] a living natural world, human beings and societal institutions co-create satisfying ways of living.” To my mind, value theory is about how not to become a society of Pessoas.

Instead, it can help guide us in producing a form of wealth that shows up in our direct experience of the world. It’s about how we navigate the question of what kinds of humans we wish to become, and what kinds of structures we design to propel us in that direction. Value theory is a matter of becoming, concerning the questions of what we wish to become, what we are becoming, and how institutions structure that process.

The anthropologist David Graeber puts this explicitly, writing of ‘value’ as the social process of drawing possibilities down from the space of what could exist, into the realized world of what does exist. Value, he writes, is the coordinated social embodiment of creative potentiality:

“However elusive, creative potential is everything. One could even argue that it is in a sense the ultimate social reality … social both because they are the result of an ongoing process whereby structures of relation with others come to be internalized into the very fabric of our being, and even more, because this potential cannot realize itself—at least, not in any particularly significant way—except in coordination with others. It is only thus that powers turn into value.”

Value debate has not exactly disappeared. Instead, there was a victor, and the alternatives were banished to the shadows. The problem is that the reigning theory of value – marginal utility theory, though what many people call ‘neoliberalism’ works too, as indicative of an economic paradigm that equates value with price – points us precisely in the Pessoan direction. It is a theory of value (prices) that undermines the actual stuff of value (phenomenology).

The philosopher Martin Hägglund writes that today’s reigning theory of value is “inimical to the actualization of freedom”, that we have created a form of progress that achieves its opposite:

“The very calculation of value under capitalism, then, is inimical to the actualization of freedom. Indeed, the deepest contradiction of capitalism resides in its own measure of value. Capitalism employs the measure of value that is operative in the realm of necessity [means] and treats it as though it were a measure of freedom [ends]. Capitalism is therefore bound to increase the realm of necessity and decreases the realm of freedom."

Hägglund’s own interrogation of value theory led him to advocate for a transition from capitalism to a form of democratic socialism that values 'socially available free time'. For Graeber, value theory provides a starting point “if one is looking for alternatives to what might be called the philosophy of neoliberalism”.

On my view, value theory provides a helpful schema to navigate the paradox of progress undermining phenomenology.

This essay steps in that direction, proposing a theory of value that begins in biology, through cognitive science, and extends all the way into economic policy. It provides both a theory of what creative potentials we ought to bring into the world, and the associated strategy for how.

My thesis, in brief:

Value is the positive flow of vitality into a living system. Over-reliance on markets is undermining the production of value. A strategy of ‘unconditionality’ can help realign progress with the production of real value.

In particular, I’m interested in tracking how value has grown overdetermined by markets, undermining the vitality of all sentient life. But inversely, this suggests a way forward. Through a strategy I will describe as unconditionality, or the sustainable, unconditional provision of a growing baseline of resources to all citizens, we can introduce a cleavage between markets and value. These cracks are directly proportional to a realignment of the production of value with vitality, of progress with phenomenology.

As Leonard Cohen chants, these cracks are “how the light gets in.”

...

The remainder of this essay is organized as follows.

I) First, I'll define a form of wealth that can map onto ideas in cognitive science, and construct a theory of value with "vitality" at its core.

II) Second, I'll use this new form of value to explore how over-reliance on markets, which drives the reduction of value to price, undermines more expansive value production.

III) Third, I elaborate the strategy I call “unconditionality”, and how it provides a method of re-coupling economic progress with the production of value.

IV) Fourth, I survey important critiques to my argument regarding unconditionality and value, in the hopes of showing where further inquiry might look.

In we go.

...

Revaluing Value: Value Is Vitality

...

The Flow of Value

Economists often define value and wealth in relation to each other. We can use the framework of stocks and flows to make sense of their relationship. Value is a flow, and wealth is a stock.

Stocks represent a fixed quantity at a given point in time. Like the stock of cars in operation in the US in 2021, which was roughly 283.3 million. Flows represent rates of change, measured over intervals of time. For example, the production of cars in the US in 2021 – roughly 1.6 million – was a flow that increased the overall stock of cars. Flows are defined in relation to the stocks they affect.

Value, as I will argue, is a matter of vitality. If value is the positive flow of vitality into a living system, wealth is that system’s stock of vitality.

...

The Stock of Wealth

So, value and wealth are different measures of the same thing. The question of value is to ask what wealth is.

The stuff of value and wealth is a category that, historically, changes. As the understanding of this stuff changes, so does the character of society. The Ancient Greeks took the stuff to be free time, made possible by slaves and women. The philosopher Hannah Arendt tells us:

“...the wealth of a person therefore was frequently counted in terms of the number of laborers, that is, slaves, he owned. To own property meant here to be master over one’s own necessities of life and therefore potentially to be a free person, free to transcend his own life and enter the world all have in common.”

For classical economists like Adam Smith or David Ricardo, value was a matter of how much toil and trouble a thing could save us. For Karl Marx, value was the congealed labor power embodied in its fruits. For marginalists, value is the marginal utility provided by an additional good or service, which is a subjective valuation revealed through prices.

Curiously, this progression strikes me as exactly backwards. Our societal definition of value has (d)evolved from free time and the exclusion of necessity-driven action from life, to reducing toil and trouble, to merely anything that generates a price.

Against this trend, let’s reconsider. What is wealth?

...

You Do Not Trade Wealth (wealth is the purpose of exchange)

Wealth has come to mean an accumulation of resources that can be exchanged for other things. To be wealthy is not to have anything in particular, but optionality and potential. The question of what wealth ought to be exchanged for is private and personal. Wealth remains a means towards privately chosen ends.

This is how we can wind up with a society of some fabulously wealthy individuals, who in fact, in the final analysis, have very little worth having. Very little of value.

In contrast, I want to define wealth as precisely that which all exchange endeavors towards. Wealth is the desired culmination of exchange. It is not a means, but an end (or, more confusingly, wealth is both means and end).

The French social philosopher André Gorz writes that when “the economy ceases to dominate society, human forces and capacities cease to be means for producing wealth – they are wealth itself.” Wealth, he writes, is the activity that develops human capacities:

“The source of wealth is the activity that develops human capacities or, more specifically, the ‘work’ of self-production that ‘individuals’ – each and all, each in their multilateral dealings with all – carry out on themselves. The full development of human capacities and faculties is both the aim of activity and that activity itself – there is no separation between the aim and the ever incomplete pursuit of the aim.”

Gorz calls wealth that is both a means and and end, where there is no separation, “intrinsic wealth”, which is “neither measurable nor exchangeable”. But can we be more specific? What is intrinsic wealth, beyond vague allusions to ‘human capacities’, or as Marx might say, the “absolute working-out of [humankind’s] creative potentialities”?

What is the common end that all means of exchange serve? Can there be a science of intrinsic wealth that does not sacrifice the understanding of wealth as an end, but still provides an analytically useful tool to help guide our policymaking, and ultimately, world-building?

I believe there already is, but it’s being developed out of sight of economists. Beyond what Gorz calls the “hegemonic ambit of economic categories”, an interdisciplinary effort is emerging at the confluence of biology, cognitive science, and philosophy. Loosely, the space is called “enactivism”, a domain of cognitive science. Therein, they’ve developed an understanding of value that roots it in evolutionary processes much larger than the merely human.

Intrinsic wealth, on this view, can be refined into a feature of phenomenology that arises as living systems engage their environments. Here, value is not an original economic category, but an aspect of the evolutionary process of life itself. To understand value, we can look to its roots, in biology.

...

Finding Value Amidst the Enactivists

The key enactivist point is that living systems do not just perceive what already exists ‘out there in the world’. The mind is not a passive representation constructed on perceptual information merely received from their environments. The mind, including the world it beholds, is a dynamic process that arises as an organism interacts with its environment.

Living systems, as they engage with their environments, give rise to aspects of the world they perceive. As some cognitive scientists write, living systems engage in “transformational and not merely informational interactions: they enact a world.”

What first caught my eye, and suggested value theory may find some roots in cognitive science, was one of the stated direct consequences of living systems enacting their worlds: “the primordial structure of value”.

“The primordial structure of value … manifests in what can now be called the subjective dimension even for the simplest organisms … A world without organisms would be a world without meaning; and it is in life’s incessant need, that a subjective perspective is established.” (source)

...

Value Is Significance Is Valence

This is where I believe we can begin building our theory of value. In establishing a ‘subjective perspective’, the ‘primordial structure of value’ is ‘manifested’. Let’s delve into this.

On this view, a living system comes with an inbuilt purpose: to exist (see: the free energy principle). This incessant ‘drive to exist’, or 'self production', common to all living systems, generates a mode of being that the philosopher of cognitive science Evan Thompson calls “concern”:

“…self-production generates ‘concern,’ an endogenous interest in or motivation for self-preservation and self-enhancement; such ‘concern’ is a form of existence or mode of being, not a mental state; and it instantiates a locus of subjective value in an otherwise valueless and subjectless world.”

The biologist Andreas Weber writes that to exist in this mode of concern is to be “already embedded in value-creation”:

“As living organisms, we as biological creatures are already embedded in value-creation…Bringing forth a body follows a primary goal – to exist. This puts a universal grid of good and bad over the perceived world. Being an organism means constantly producing existential value. So we need to recognize our bodies and emotional existence as sources of value prior to deliberating about which theory of value may be best.”

Here, ‘existential value’ has something to do with navigating these perceptual grids of good and bad, seeking out the good. But succeeding is a pre-reflective category that registers in the body, and our “emotional existence”.

But Weber’s description is vague. Can we be more rigorous? In Enaction, Di Paolo, Rohde, and De Jaegher describe things in greater detail:

“…organisms cast a web of significance on their world. Regulation of structural coupling with the environment entails a direction that this process is aiming toward: that of the continuity of the self-generated identity or identities that initiate the regulation. This establishes a perspective on the world with its own normativity…Exchanges with the world are thus inherently significant for the agent, and this is the definitional property of a cognitive system: the creation and appreciation of meaning or sense-making, in short.”

To sense-make is to exist in the mode of concern, as Thompson wrote. It’s to navigate these ‘universal grids’ or ‘webs of significance’ that living systems ‘cast’ onto their perceived world, in pursuit of continuing their existence. Given a vast landscape of potential actions, living systems act so as to move themselves in the direction of what Di Paolo & friends call “significance”, or what Weber called “existential value”. Note that value and significance are being used as synonyms.

Evan Thompson gives three pillars of the sense-making process:

(1) “sensibility as openness to the environment (intentionality as openness)

(2) significance as positive or negative valence of environmental conditions relative to the norms of the living being (intentionality as passive synthesis— passivity, receptivity, and affect)

(3) the direction or orientation the living being adopts in response to significance and valence (intentionality as protentional and teleological).”

The second condition caught my eye, because recall that “significance” and “value” are often used synonymously by enactivists. Significance is value. I conferred with Thompson in the Public Square (Twitter), and he loquaciously confirmed that enactivism takes the two as synonyms:

With this in mind, we can rewrite the second pillar of sense-making, showing the enactivist theory of value:

(2) value as positive or negative valence of environmental conditions relative to the norms of the living being.

So, significance is value is valence. What’s valence? Valence refers to the overall subjective feeling, or pleasantness, of a particular experience. Joy, uncontrollable laughter, and the aroma of a freshly-cooked favorite meal all have positive valence. Sadness, fear, or anxiety all have negative valence. When I quoted Weber above, saying “we need to recognize our bodies and emotional existence as sources of value”, valence is the source of value he has in mind. Positive valence is a sort of signal that indicates we’ve ventured towards the good, or that which may help sustain our existence.

For enactivists, value is the valence brought forth, or enacted, by a living system as it engages with its environment. The more positive the valence, the higher the value.

But if we were to stop here, then our theory of value would simply define ‘vitality’ as positive valence. Anything that feels pleasant would have value, and society’s normative direction would be that of increasing pleasantness.

Were this the case, you may justifiably respond that we’ve simply reinvented hedonism with some lipstick on. On the surface, this theory of value could not distinguish between heroin addicts with an infinite supply and truly vibrant, radiant, value-brimming human beings.

So we have one final jump to make: how do we get from positive valence to vitality?

...

From Valence to Vitality

Again, let me provide the destination at the outset. Vitality is a subcategory of positively-valenced experiences where the experience raises our hedonic set-point, or the positive valence of our baseline state of consciousness through time.

Or: vitality is a set of positively-valenced experiences that kick-off positive feedback loops to sustainably raise average levels of positive valence over time. In this way, vitality maps onto Gorz's idea of 'intrinsic wealth', in that it is both a means towards generating more vitality, while simultaneously the end-goal in itself. But let me explain.

Some types of positively-valenced experiences are simple up-and-downs, like going to my favorite jazz bar with a close friend. We go out, have a great time full of positive valence, and then go home, where valence returns to it’s average level.

Others are up-and-down-and-farther-down, like taking heroin. These provide short-term boosts of positive valence, but the come-down does not merely return us to normal. It pushes our baseline lower. Andrés Gómez Emilsson (director of research at the Qualia Research Institute) writes that whether a strategy is truly in line with a long-term view of hedonism depends on the kinds of feedback loops it instantiates. Common examples of why hedonism is undesirable, from drugs to sugar, are short-sighted because they trigger negative feedback loops that undermine hedonic set-points. It’s just bad hedonism:

“Amphetamines, traditional opioids, barbiturates and empathogens can be ruled out as wise tools for positive hedonic recalibration. They are not comprehensive life enrichers precisely because it is not possible (at least as of 2016) to control the negative feedback mechanism that they kick-start. Simply pushing the button of pleasure and hoping it will all be alright is not an intelligent strategy given our physiological implementation. The onset of this negative feedback often triggers addictive behavior and physiological changes that shape the brain to expect the substance.”

Other types of positively-valenced experience bring us up, but as we come down, we settle at a slightly higher set-point, or valence equilibrium. An example could be a successful psychedelic therapy session, where a deep-seated trauma is surfaced and mended, such that when we return to sobriety, our baseline psychological state is slightly enhanced. Another example could be a worker who transitions from a dehumanizing work environment to an enriching one. Moving from being a powerless cog in an unthinking production regime to a human with voice, power, and the opportunity to meaningfully engage with both the content and process of their work. This provides a lasting boon to average valence levels, kicking off a positive feedback loop.

Vitality is this third category: any positively-valenced experience that generates a feedback loop towards sustainably raised set-points of positive valence. Put differently, vitality is a property that describes those experiences that sustainably make us feel more alive. Vitality is self-perpetuating positive-valence. Vitality is the growth of life2.

...

We've now covered, however briefly, the first sentence of my hypothesis:

Value is the positive flow of vitality into a living system.

Let's dig into the following two:

Over-reliance on markets is undermining the production of value. A strategy of ‘unconditionality’ can help realign progress with the production of real value.

...

Markets are Constraining Value

“…it strikes me that if one is looking for alternatives to what might be called the philosophy of neoliberalism, its most basic assumptions about the human condition, then a theory of value would not be a bad place to start. If we are not, in fact, calculating individuals trying to accumulate the maximum possible quantities of power, pleasure, and material wealth, then what, precisely, are we?” (David Graeber)

So. Every living system confronts a landscape of possibility at every moment. We perpetually face a branching tree of behavioral paths we may take. The ‘creative potentiality’ Graeber mentions. Primordially, value evolved as a sort of perceptual heat map superimposed over the possibility landscape. The map helps us choose what to do, given the possibilities. We go in the direction of value.

But these maps aren’t perfect, and the process is evolutionary trial and error. More often, we go searching for value. That is, we take action, and discover whether that behavioral path struck a wellspring of value, or not. We take a new job, start a new hobby, kickoff a new exercise regiment, in the hopes that they'll make us feel more alive. Life is a generational search party for higher gradients of value within the possibility landscape.

The question of value, then, is a question of how free we are to explore the possibility landscape. The wider the possibilities we face, the more diverse the forms of life we may enact, the greater the odds that we bring forth deeper pools of value.

And this is where today’s theory of value - the marginal utility theory - becomes a problem.

...

The Marginal Utility Theory of Value

Marginal utility theory claims that value is set by the additional satisfaction (utility) that one extra (marginal) unit of a good or service provides.

Within the universe of equations, you can directly measure, and so manipulate, marginal utility. But in the real world, you can’t. My brain doesn’t give off some utility reading, nor is it a neurochemical whose levels can be monitored. This is because utility doesn’t actually exist, making its measurement a problem.

The economist Paul Samuelson bypassed the problem by suggesting there's no need to measure utility, since rational agents will 'reveal their preferences' through markets. And preferences are ultimately expressions of utility.

So prices are now used as the best indicator of marginal utility. This whole theory is often reduced (usually by critics) to “price equals value”. The theory assumes that consumers and producers will adjust their respective consumption and production levels until prices equal marginal benefits across the economy. Once the costs of production equal its marginal benefits, and the prices of goods and services equal the marginal benefits of consumption, you have an efficient market where prices reflect value.

As one economics textbook puts it:

“Value will be the actual price once all the producers and consumers have had time to adjust their consumption and production to any changes in taste and/or technology. In other words - aside from the time frame - there is no difference between value and price according to this theory.”

So ‘price equals value’ is a relatively fair encapsulation of the theory. This is where a problem arises. Value theory, as we’ve described it, is about the flow of vitality into living systems. Marginal utility theory, however, is about why diamonds are priced so much higher than apples.

Marginal utility theory is a theory of prices that presents itself as a theory of value. And in that conflation, value is undermined.

...

Price Should Not Equal Value

There are many economic critiques of marginal utility theory. But usually, these critiques do not attack its explanation of price differentials. They critique its conflation of value with price. They point out all the ways that letting a theory of price determine value actually undermines an understanding of value worth pursuing.

So perhaps the better program is to ask how to let marginal utility theory simply be what it is, a theory of price differentials, without having it also determine the normative category of value. Prices be what they may, value may lie elsewhere.

The question to ask is then: what are the conditions that lead a theory of prices to dominate value theory, and can they be untangled?

A hypothesis: prices will dominate value in direct proportion to the centrality of markets in society. The degree to which agents in an economy are compelled to participate in markets is also a measure of the degree to which they are compelled to accept the market’s form of value, which will always be controlled by prices.

This does not suggest that to liberate value from prices we need to abolish markets. Instead, we can reduce the singularity of markets in the social provisioning of resources by empowering alternative methods. The most direct alternative might be managing resources as a commons, defined by the legal scholar Brett Frischmann as a resource “openly accessible to all within a community regardless of the entity’s identity or intended use.” Public goods, too, are unconditionally provisioned goods or services, generally managed by a public entity and funded by government spending.

It’s beyond the scope of this essay to delve into exactly which resources should be provisioned through markets, which should be managed as commons, and which should be provided as public goods. But as a basic delineation, Frischmann points out since markets can only value that which can be priced, and therefore captured by private entities, markets are sub-optimal modes of provisioning resources with the potential for positive externalities:

“…the market mechanism exhibits a bias for outputs that generate observable and appropriable returns at the expense of outputs that generate positive externalities [public benefits that cannot be captured by market players]. This is not surprising because the whole point of relying on property rights and the market is to enable private appropriation and discourage externalities. The problem with relying on the market is that potential positive externalities may remain unrealized if they cannot be easily valued and appropriated by those that produce them, even though society as a whole may be better off if those potential externalities were actually produced.”

In other words, open-access to certain kinds of resources can lead to ‘scale returns’ – “greater social value with greater use of the resource.” Markets prevent these scale returns. Frischmann goes on to argue that any resource that can be categorized as “infrastructure” has a strong basis for commons management.

Returning to our focus, we find that markets, by their very design, can constrain the social value resources might otherwise provide. If price governs all value, the constraint is absolute. But if markets are reduced to merely one mode of provisioning among an empowered ecosystem of alternatives, the scope for value production expands.

…

Socially Necessary Labor Time

What does it mean, in practice, to reduce the centrality of markets in society? Let’s look at labor markets, which provide a clear example of how over-reliance on markets can function as a constraint on value.

When price governs value, labor markets are a massive source of producing value. Every dollar earned in wages is a unit of value produced by the economy. Since citizens require access to a certain amount of resources to live, and labor markets are the primary method of provisioning these resources, participation in labor markets is widespread. Generally, every society strikes a balance of how much time citizens exchange on labor markets. In our case, roughly 40 hours a week.

From a price-equals-value perspective, this is good. Employed citizens produce value both by earning wages, and by helping businesses generate revenue. The system has little incentive to reduce the necessary labor time citizens must exchange for the resources they need to survive, as doing so would reduce value in terms of price.

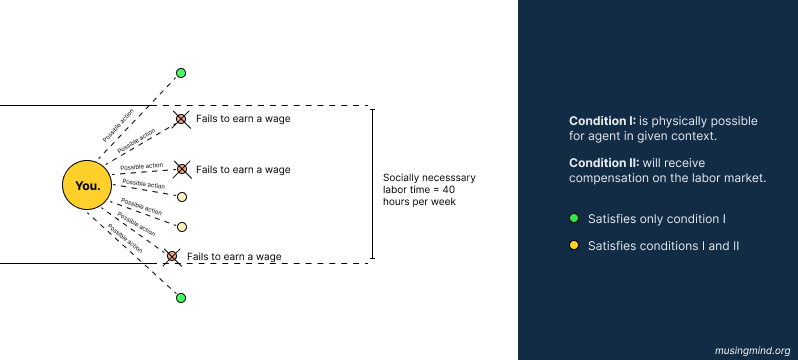

But from a value-as-an-evolutionary-search-for-vitality perspective, things appear differently. What is labor time? It’s a constraint on the actions we are free to take, and ultimately, the forms of life we are free to enact. For those 40 hours per week, we can only behave in ways that 1) are physically possible for a given agent, and 2) earn a wage.

By contrast, leisure time (simply understood as non-labor time) is expansive. The second constraint – the imperative to earn a wage – is removed, widening the possibility landscape of the forms of life we are free to enact. In the evolutionary search for value, wider possibilities lead to greater diversity, and greater chances for adaptive selection.

We can formalize this labor market constraint. Karl Marx used the term socially necessary labor time (SNLT) as the measure of a commodity’s value. SNLT was the average amount of time necessary to produce something across all society’s producers at a given moment in time. If across all producers in 1850, it took 10 hours to produce a table, the SNLT of a table, and therefore its value, was 10 units.

But we can expand this measure from the production of commodities, to the production of human life, and in particular, as a measure of the constraint placed upon value.

If across all society in 2022, it takes an average of 40 hours of labor time per week to sustain a dignified life, we can say that the SNLT of life today is 40 units. We can then visualize this measure as a constraint on the possibility landscapes individuals face.

Above, I described how every moment, every week, every year presents a branching tree of behavioral possibilities. Socially necessary labor time defines a boundary of possibility, inside of which any action must not only satisfy the condition of being physically possible for the given agent, but must also be rewarded on the labor market.

Within the temporal boundary of SNLT, all possible actions are forced to satisfy an additional condition, which restricts the overall variety of possibilities, and thus the aggregated forms of life available for me to enact, and thus, my potential scope of value production. Here’s the visual at 40 hours:

Reducing SNLT shrinks the temporal boundary around my possible courses of action, increasing the number of possibilities that need only satisfy the first condition. In doing so, more actions become possible, widening the evolutionary search for value production:

It’s in this spirit that Martin Hägglund proposes “socially available free time”, the inverse of socially necessary labor time, as a measure of freedom:

“The key to the critique of capitalism is therefore the revaluation of value. The foundation of capitalism is the measure of wealth in terms of socially necessary labor time. In contrast, the overcoming of capitalism requires that we measure our wealth in terms of what I call socially available free time…The aim of the revaluation of value is to transform our conception of social wealth in such a way that it reflects our commitment to free time. The degree of our wealth is the degree to which we have the resources to engage the question of what we ought to do with our lives, which depends on the amount of socially available free time. To be wealthy is to be able to engage the question of what to do on Monday morning, rather than being forced to go to work in order to survive.”

In other words, Hägglund's view of freedom can be read as progressively reducing the constraints placed on our decision making. I add that not only is this inherently desirable on the grounds of freedom, but also in terms of widening the evolutionary net our species casts out into the possibility space, in search of forms of life that enact value.

To some degree, capitalist societies have always professed some degree of commitment to this measure of freedom. Progress was once widely seen as the transformation of our lives from labor to leisure. But in every age, from Marx, Henry George, to Martin Hägglund, critics have argued that there is something intrinsic to the structure of capitalism that prevents it, even while ostensibly working towards it.

In our context, we might say that the responsible party is price as the measure of value, which by definition, constrains socially available free time (labor time generates value through wages, free time does not).

Against the idea that simply doubling down on innovation, productivity, and economic growth will deliver us a freedom worth having, economists such as John Maynard Keynes argue that “the system is not self-adjusting”:

“None of this, however, will happen by itself or of its own accord. The system is not self-adjusting, and, without purposive direction, it is incapable of translating our actual poverty into our potential plenty.”

So the question: how to adjust the system? How to employ our great accumulation of means towards ends worthy of human life, dreams, and potentiality? How to transmute the endurance of tedium towards an experience of life more vibrant, more alive? How might we ask the same question of economic design that the architect Christopher Alexander asked of building: “how can we create more life in this world?”

I believe one piece of the answer is a broad commitment to the principle of unconditionality.

...

The Road to Value Is Unconditional

Markets are overdetermining the production of value. Humans spend an unnecessary amount of time working unnecessary jobs that slowly gnaw away at our vitality, the stuff that might otherwise impel spirited action. Investment chases after quick dollars, regardless of the ecologies it leaves barren, crises it leaves unaddressed, or social possibilities it leaves unexplored.

The strategy of unconditionality offers one potential alternative by progressively opening a space between markets and value. The larger the space between them we create, the more expansive the adjacent possible grows. The greater the evolutionary probability society gains, as itself an evolutionary system, in enacting greater sources of value.

...

What Is Unconditionality?

By unconditionality, I mean the unconditional provisioning of access to resources for all members of society, with no preconditions beyond citizenship.

This idea is nothing new, and we already do it plenty. Economics generally calls unconditionally provisioned resources “public goods”. They’re usually described as having two main qualities. Public goods are non-rivalrous (one person’s use of the good does not detract from another’s), and non-excludable (one person cannot exclude another from the good’s benefits). Common examples include national defense, transportation systems, law enforcement, and access to drinking water. Digital technologies are growing the list, adding examples like open source software and data, and even the internet.

Frischmann folds public goods into a broader category he calls infrastructure. Infrastructure is the substrate of resources productive activities draw and take place upon. Crucially, he notes the role infrastructure play in determining the scope of possible behaviors for all agents within a system, expanding or contracting the line that separates the possible from the impossible:

“Infrastructure resources are intermediate capital resources that serve as critical foundations for productive behavior within economic and social systems. Infrastructure resources effectively structure in-system behavior at the micro-level by providing and shaping the available opportunities of many actors. In some cases, infrastructure resources make possible what would otherwise be impossible, and in other cases, infrastructure resources reduce the costs and/or increase the scope of participation for actions that are otherwise possible.” (Infrastructure: The Social Value of Shared Resources).

Unconditional programs may be seen as adding to the stock of infrastructure supporting all citizens. Expanding the examples, we can add programs such as:

Basic income: adding a baseline of income to the infrastructure of modern life by unconditionally provisioning of a baseline of income to all citizens.

Universal healthcare: adding healthcare to the infrastructure stock by unconditionally provisioning access to healthcare for all citizens.

Baby bonds: adding an inheritance to modern infrastructure by unconditionally provisioning a one-time inheritance to all citizens.

Public education: Adding education - you can see the pattern here.

Public internet: the pattern continues.

Natural resource dividends: adding a variable, regular dividend from tax revenues on natural resource use, such as land, carbon, broadband spectrum, and fisheries.

And so on. The point here isn’t to motivate any particular unconditional program, but to see it as a mode of provisioning that can expand the sphere of value production.

Unconditionality serves the production of value through its effect on socially necessary labor time. Visualized simply, the more access to non-market resources one has, the lower the constraint of socially necessary labor (market) time:

...

What Does Unconditionality Do?

Two features of unconditionality:

- Unconditionality directly mitigates socially necessary labor time, expanding people’s scope of possible behaviors and forms of life.

- Unconditionality supports the creation of both illegible value, and value cloaked by illegibility.

We've dwelled on the first feature enough, but let's look at the second.

…

Unconditionality supports the creation of both illegible value, and value cloaked by illegibility.

Recall that Gorz described a form of ‘intrinsic wealth’ that is neither measurable nor exchangeable. This stands at odds with the conflation of price and value, since what resists measurement and exchange cannot enter into the calculus of GDP. From the perspective of a managerial state, this is no good, since only what gets measured can get managed.

Unconditionality, then, may foster forms of value that a centralized, managerial state tends to avoid. To be more precise: unconditionality allows for the creation of both illegible value, and value cloaked by illegibility.

Illegible value is simply value that resists measurement. The value of a close-knit community, or a cool breeze while strolling through a sunny park, and that brief moment of closing your eyes and feeling radiantly at ease.

Above, Frischmann noted that markets are biased towards investing in outputs “that generate observable and appropriable returns”. When value is seen as the positive inflow of vitality, there exists a huge range of valuable activities that markets simply have no reason – i.e., no observable and appropriable returns – to invest in. Unconditionality then provides a substrate of resources that can support such activities, since the resources require no exchange, and therefore, no unit of equivalency that would demand legibility of the returns.

Value cloaked by illegibility is a potentiality that preexisting maps, methodologies, and measurements cannot easily foresee. The profit motive tends to allocate capital towards value-potentials that can be seen ahead of time, narrowing the scope of investment, and shaving off potential value.

Unconditionality provides resources that, by virtue of demanding nothing in exchange, can explore a wider range of potentialities, and therefore, chart deeper into the territory of surprise, where value roams.

...

Unconditionality and Vitality, In Practice

This all sounds nice, but how would understanding value as vitality work, in practice? Conceiving of value as price motivates an institutional strategy of pursuing economic growth, or the increase of the production of price (GDP). GDP, as the numerical proxy for value, fits cleanly into the algebraic equations and econometric models that motivate academic consensus and policymaking. GDP also provides a very simple category for public discourse, facilitating communication between experts and the general public.

If we re-conceive value as vitality, what changes? First, since price is no longer held as a suitable proxy for value, we lose the single, numeric proxy that GDP offers. An idea that is gaining support in theory, if not practice, is to fill the void left by GDP with a more multi-dimensional ‘dashboard approach’. Instead of one number, we can look to a dashboard of 3, or 5, that doesn’t reduce everything into a single metric. We already have a number of interesting dashboard approaches, including the OECD’s Better Life Index, the Human Development Index, and Miranda & Snower’s SAGE Framework.

But dashboard approaches still place a proxy on value. Proxies that help us measure what’s important are necessary. But we have this tendency to forget that all proxies are imperfect. The map is not the territory, and whatever the proxy is blind to grows institutionally neglected. This is where we can find a direct connection between the view of value as vitality and an institutional strategy of unconditionality.

As discussed above, unconditionality offers a method of supporting those elements of value production that are illegible to the proxies – however expanded and multi-dimensional – we use. Think of it as an insurance policy for progress. An expanded dashboard of proxies may help cast a wider net over what gets measured, while a complementary policy of unconditional acknowledges both that we cannot measure everything, and yet there is value in supporting precisely that which resists measurement.

...

Who Pays For Unconditionality?

A quick point: unconditionality is not free. Unconditionally provisioned resources are free at point of access, but are still paid for elsewhere, generally via government spending3. From the perspective of the economic system on the whole, making a resource universally available is, in fact, quite expensive.

What unconditionality affords is the ability to customize where the cost-burden of a resource falls. For example, consider moving from private to universal healthcare. Individuals no longer have to pay monthly premiums, and are guaranteed access to health services. But the costs premiums represented don’t just disappear. Instead, the cost is shifted to government spending, and eventually offset by taxation.

This allows a society to use taxes like beavers building dams. We can steer capital away from destabilizing and unearned accumulations (land rent, value extraction, monopoly power), diverting resources to the public as unconditionally provisioned ‘infrastructure’ that expands the scope of possibility for the average citizen, while generating positive externalities and scale returns.

Society, then, pays for unconditionality, and should do so when the resources provisioned can foster more value than when provisioned via markets.

But this also raises concerns. If unconditionality comes at significant cost, then it carries tradeoffs that should place a limit on its scope. Every dollar spent on unconditional programs is one that could've been spent elsewhere, and no matter how potent it maybe, unconditionality alone is inadequate. It must operate alongside a spectrum of other strategies (especially those aimed towards 'predistributive' improvements). To get a sense of what unconditionality might look like in practice, let's explore these concerns.

...

What If Unconditionality Makes us Lazy?

Perhaps the most prominent concern is found in another term often used to describe unconditional resources: handouts.

Unconditional resources may allow citizens to scale back their participation in labor markets, but what if this works too well? Society will require active, productive participants to navigate the uncertain future. What if unconditional handouts create a huge demographic of lazy, unproductive citizens who subsist off resources that are taxed away from those who still work? And what if doing so undermines the tax base that funds unconditional programs in the first place?

This line of critique is both important and instructive, so let’s probe a bit.

…

Unconditionality is not a binary. We don’t either provision unconditional resources or not. Already today, we’re the beneficiaries of a massive substratum of unconditionally provisioned resources and public options. From transportation and communication infrastructure, libraries, rule of law and protection, education, healthcare and childcare benefits (in some countries), to open-source software and digital commons (like Wikipedia).

Society itself is a growing accumulation of unconditional benefits. The political economist Henry George, in writing that “progress goes on as the advances made by one generation are…secured as the common property of the next”, is effectively suggesting that civilization makes progress by offering increasingly generous handouts to all citizens.

The relevant, critical question is thus not whether unconditionality might sink society, but how much? Is there a threshold beyond which too much unconditionality actually undermines the long-term production of value, and if so, where does that threshold fall?

In terms of this essay, we might ask: how low can socially necessary labor time go before it transitions from a gift to a curse, whether by means of undermining production, or requiring such large sums of public funding that taxes reach confiscatory, unjust levels?

…

Since this is a question of thresholds along a spectrum, let’s contextualize the spectrum. On one end, there is simply society as it is today, with no further commitments made to unconditionality. Here, socially necessary labor time remains around 40 hours per week. On the other end, socially necessary labor time drops to zero, whether by means of a ‘fully automated’ society, innovations that skyrocket productivity, or whatever.

Often, unconditionality is objected to on the grounds that a socially necessary labor time of zero would both undermine productivity and require unjust, unsustainable levels of taxation. Maybe so, but I find the middle-ground both much more compelling, and much more viable. My view does not call for the abolition of markets, labor or otherwise, but placing them on equal footing with alternative modes of provisioning resources.

For example, from 1830 until around 1940 (excluding the Great Depression), socially necessary labor time was already steadily declining. Then, it stopped:

The campaign to reduce the working week was rooted in a strong labor movement. In the late-20th century, the labor movement was stripped of power and reach, alongside a cultural turn against the value of leisure time (and about a million other things that happened around 1971).

If trends had simply kept their pace, socially necessary labor time might’ve continued declining to around 27 hours per week today:

So the first benchmarking question is whether being free to work an average of 27 hours per week – not zero – would undermine productivity, or require unsustainable taxation. I don’t find either concern compelling here (but I'm also struck by the lack of rigorous research on this question). If undermining labor’s bargaining power (alongside a broad package of neoliberal reforms) was sufficient to flatline the trend, we might assume that the inverse – continuing to strengthen labor’s bargaining power, alongside social democratic reforms – could’ve continued the trend (admittedly, this is an impossible assumption, but the virtue of a blog is you can make these anyway, and hope others will develop the idea more rigorously).

Such reforms, whether empowering unions and labor standards, widening the coverage of sectoral bargaining agreements, minimum wages, stronger antitrust, or even public retirement accounts, are not very expensive, and do not threaten confiscatory tax levels.

What about productivity? One data point to look to is France, who reduced their work week from 39 to 35 hours back in 2000. 20 years later, the results in terms of welfare and working hours have been mixed, but small. In terms of employment, not all that much appears to have changed, certainly no mass migration from the workforce. Trends in growth rates and productivity appear unfazed. I struggle to imagine that another 8 hours would spell the demise of society4.

But what if we carry this further. Let’s assume that in the 1970’s, we strengthened labor institutions, more industries came under coverage of sectoral bargaining agreements, and this delivered us to the socially necessary labor time of 27 hours per week, mostly driven by higher wages and benefits.

Now, on top of that, let’s imagine the politically far-fetched. We pass not one generous unconditional program, but a whole suite of them. Let’s imagine that in an alternate 2020, on top of strong labor institutions bargaining with employers, we enjoyed the benefits of public internet and healthcare, universal basic income, annual dividends from a social wealth fund, and a citizen’s inheritance from baby bonds.

If you tally each of these up in their most generous forms, each citizen would receive, on average about $20,000 per year in unconditional cash transfers, plus access to healthcare and internet. But let’s note the important caveat that, since these would all require offsetting taxes, beyond a certain threshold of income, citizens would either be breaking even (paying $20,000 more in taxes while receiving the extra $20,000), or being net funders rather than recipients (since the elevated taxes would eventually outweigh the benefits they provide. The Zuckerberg’s of the world do not get an extra boost).

This being on the farther end of the conceivable spectrum, what might happen? In 2020, roughly 35 million Americans lived on $20,000 or less of earned income, so roughly 10.5% of the population could stop working entirely and receive the same level of income. Whether they would is a different question, which current empirical research does not support5.

Of the remaining 90% of citizens, you have two groups. Those who make more than $20,000 but not enough to be beyond the threshold of those who break even, and those who make enough to pay more in elevated taxes than they receive from the unconditional transfers. Contra neoclassical economics, there isn’t much evidence supporting the idea that raising taxes on the wealthy reduces their labor, so let’s assume negligible reductions in work for that category.

For those between $20k and the break even point, we should expect some reduction in labor hours for some demographics. But how much? If a household earns $100,000 between two working adults, and they now each receive maybe an extra $8,000 (after taxes claw back some of the unconditional transfers), how much might they actually change their labor hours?

To jump ahead, here’s a wager. When the dust settles, and changes are averaged out, maybe socially necessary labor time settles around 20 hours per week:

At the most generous end of the spectrum of what might actually be possible to achieve given today’s level of resources and technology (according to my baseless calculations that must be improved upon) we’re looking at a socially necessary labor time in the neighborhood of 20 hours per week.

So critiquing all unconditionality on the basis of assuming a fully automated society where no one needs to work at all, just doesn’t make sense. We cannot provision enough unconditional resources to allow a significant portion of the population to live unproductive lives of lethargic leisure (neither do I think we should equate dropping out of the labor market with an absolute loss in productivity, given that some of society’s defining innovations were developed in leisure time). This section has not rebutted the critique wholesale, but hopefully, helped narrow its focus.

Instead of imagining extremes, we should explore the middle-ground. What would happen to society if citizens were free to work only 30, or 20 hours per week? To complement theoretical probes, we should explore the question experimentally. We won’t, and shouldn’t, pass the above package of unconditional programs together, overnight. Instead, these things tend to happen one at a time, piece by piece. This allows us to learn and adapt as changes ripple out in all the ways we could never predict.

...

Vitality Theory

“Vitality, understood both somatically and mentally, is itself the medium that contains a gradient between more and less. It therefore contains the vertical component that guides ascents within itself, and has no need of additional external or metaphysical attractors…” (Peter Sloterdijk)

At the outset, I could’ve motivated this essay with the charts we all see littered throughout the news. Anxiety and loneliness are on the rise; tribalism is fragmenting us into bickering groups; inequality is soaring to mind-numbing proportions; biodiversity is dying out while the glaciers melt. I could’ve quoted Graeber again: “There is something very wrong with what we have made ourselves…It is as if we have collectively acquiesced to our own enslavement.”

But I think The Pessoa Problem encapsulates the litany of gripes in a way that suggests where this is all going. Where a society that loses touch with the production of real value drives its people. We may find ourselves at the frontier of the evolution of life on earth, with unimaginable technologies and fantastically productive industries. And yet, for all our labor, and of all the potentialities we might’ve pulled down into actuality, it may yet all come “down to trying to experience tedium in a way that does not hurt.”

We don’t want to wait until we all find ourselves in the Pessoan position. The earlier we change course, the more energy we’ll have to mobilize. How miraculous, then, that we find ourselves in a moment where the world as it was appears to have cracked open! As the playwright Tom Stoppard exclaims:

"A door like this has cracked open five or six times since we got up on our hind legs. It's the best possible time to be alive, when almost everything you thought you knew is wrong."

Now is a time of high social plasticity. The Harvard political economist Paul Pierson calls it a juncture, where institutions are forged and set upon paths or trajectories that, afterwards, grow more difficult to alter. During this juncture, this moment of plasticity, this cracked-open door of dizzying possibilities, value theory can be a guide.

…

And it can begin with the observation that the production of value can no longer be left to markets alone. The invisible hand is a poor purveyor of vitality. We are less in need of the growth of mere economic activity than we are of growth in the basic triad of evolution – variation, selection, and replication. We need more variation, wider selection, and greater capacity to replicate whatever resonates. We don’t know the road to well-being in the 21st century. Growing uncertainty and volatility often cloak value, rendering it illegible to existing methodologies. But by incorporating greater measures of unconditionality, we can still design ourselves a wider scope of evolutionary freedom to go on the hunt.

Unconditionality provides a design approach that seeks to create as vast a radius of exploration as possible. A commitment to unconditionality expands the adjacent possible of all citizens. It harnesses the power of centralized provisioning to support the necessary conditions for a decentralized, evolutionary search for forms of life that enact more vitality, more value.

In a world where socially necessary labor time is reduced to 25 hours of labor per week, would you be free to live in ways that make you feel more alive? Would you be free to explore different roads to value? Now, as with the architect Christopher Alexander, let’s set out to build the world that invites more life.

Let’s build a world so vibrant, so worthy of the impossible odds we defy daily merely by being here, and being aware of our own presence, that even Pessoa, amidst the pain and suffering that will not leave us (wireheading aside), and the tedium that sets in like a weighted blanket, may, in spite of all this, swell with vitality, and come alive with the sense that life itself is a quality we can grow within us. This is the growth that matters. This is the growth that discovers, creates, and cultivates real value. This, the phenomenology of vitality, is the stuff of progress.

...

Thank you to Kate, Stephanie, and Marcus for excellent feedback on earlier drafts.

Footnotes

- Despite my coming to use this term, ‘society of Pessoas’, as in image of our demise, I should note that I love Pessoas work, and think the universe is richer for his having been around. So, enjoy the irony. (back)

- Emilsson goes on with a really interesting bit on why caloric restraints are one possible reason why we didn’t naturally evolve to maximize value in this way. But now, given the paradigmatic changes in our evolutionary environments and capabilities over the past few hundred years, we not only can, but probably should, focus on ‘real value’, or increasing our hedonic set points: “Naturally one may be skeptical that perpetual (but varied) bliss is at all possible. After all, shouldn’t we be already there if such states were actually evolutionarily advantageous? The problem is that the high-valence states we can experience evolved to increase our inclusive fitness in the ancestral environment, and not in an economy based on gradients of bliss. Experiences are calorically expensive; in the African Savannah it may cost too many calories to keep people in novelty-producing hyperthymic states (even if one is kept psychologically balanced) relative to the potential benefits of having our brains working at the minimal acceptable capacity. In today’s environment we have a surplus of calories which can be put to good use, i.e. to explore the state-space of consciousness and have a chance at discovering socially (and hedonically) valuable states. Exploring consciousness may thus not only be aligned with real value (cf. valence realism) but it might also turn out to be a good, rational time investment if you live in an experience-oriented economy. We are not particularly calorie-constrained nowadays; our states of consciousness should be enriched to reflect this fact.” (back)

- But new ideas are forthcoming, like plural funding for public goods, which is basically a fund matching program where governments and philanthropies fund projects with the most individual contributions. (back)

- France reduced the workweek by lowering the overtime threshold after which employers must pay time and a half. We can think of this is a ‘top-down’ mandate. Unconditionality, pursues an opposite, ‘bottom-up’ strategy. Rather than mandating how much people are allowed to work, we can provide them the resources to decide for themselves. Reducing socially necessary labor time reduces the amount one must work to sustain a form of life they value, but leaves people the freedom to choose otherwise, and continue however long they like. This is good, because it allows those who find their work stimulating and meaningful to dig in, while allowing those working lifeless jobs, from retail clerks to the ‘Bullshit Jobs’ documented by Graeber, to work less, which is also good. (back)

- Current empirical research on unconditional cash transfers finds that recipients, especially low-income ones, don’t reduce their hours of work after receiving unconditional cash. In many cases, they either invest in raising their productivity, or find more fulfilling and stable employment quicker than control groups. But these studies are usually looking at monthly transfers of up to $500 for a year or two, not $20k guaranteed for life. (back)

Bibiliography

An incomplete list of works that were central to this essay.

- Some David Graeber stuff: It is value that brings universes into being / Towards an Anthropological Theory of Value /

- Some enactivism stuff: The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience / Horizons for the Enactive Mind: Values, Social Interaction, and Play / Living Ways of Sense Making

- For a critique of marginalism's price = value dynamic: The Value of Everything

- Re-imagining Value: Insights from the Care Economy, Commons, Cyberspace and Nature

- André Gorz: The Critique of Economic Reason / The Immaterial

- Martin Hägglund's This Life: Secular Faith and Spiritual Freedom

- Hartmut Rosa's Resonance: A Sociology of Our Relationship to the World