Of Paradigms & Policies

December 03, 2019

Though we remain mostly unclear as to whether chickens precede eggs, or eggs precede chickens1, a sentiment is afoot that new ideological paradigms precede radical policies and structural change.

From systems theorist Donella Meadows, novelist Marilynne Robinson, to progressive economist Mariana Mazzucato, we find variations on the idea that policies emerge from paradigms, rather than paradigms emerging from policies.

This logic tells us that to supplant the status quo with a new system - one that determines not to desecrate the planet, not to let working classes languish in toil and precarity while income shares of the top 0.1% balloon - we cannot change the policies undergirding the old system before changing the collective minds that anchor old ideas.

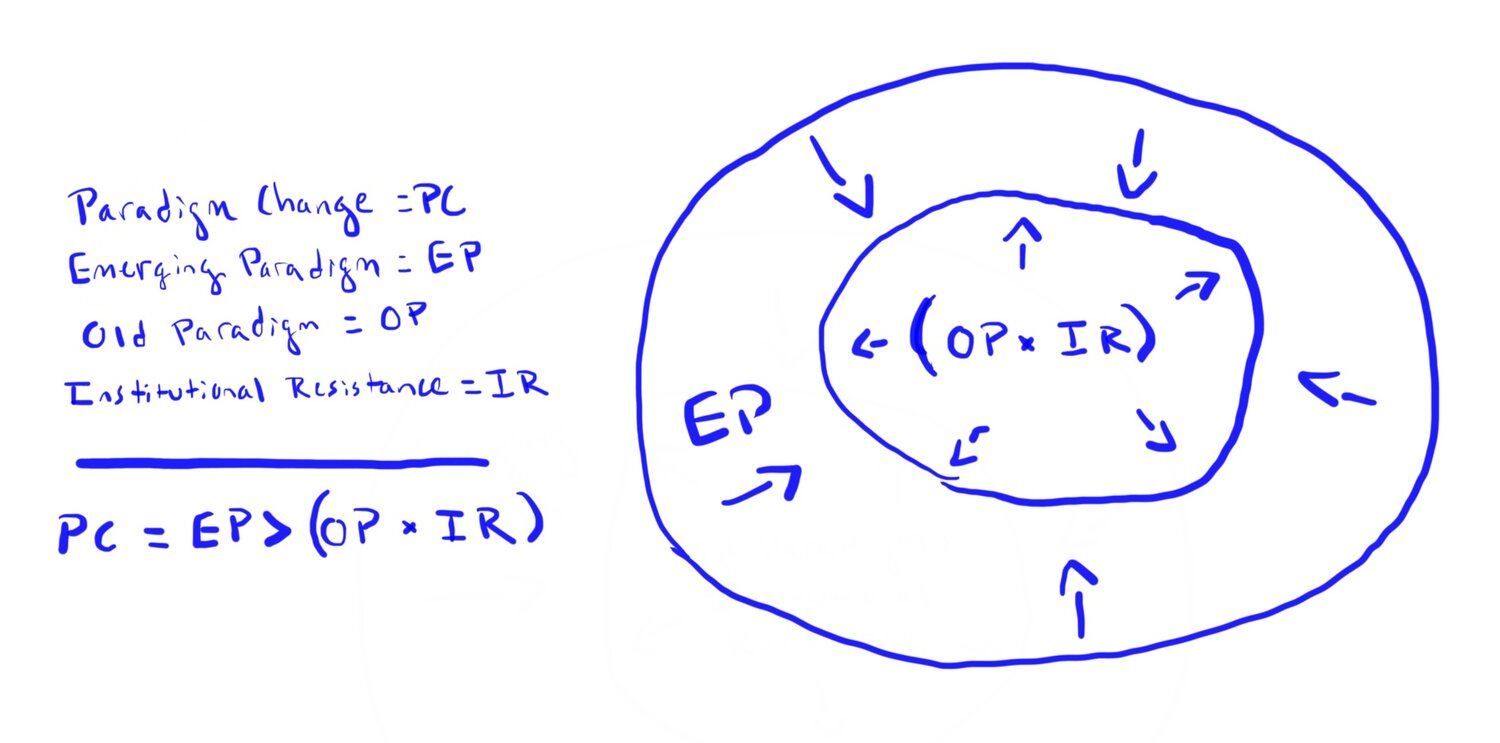

But what if we explore policies as design elements that create the very conditions from which new paradigmatic ideas emerge? What if, with a new paradigm teetering on the threshold of realization, though being beaten back by the old paradigm’s institutional resistance, policies are a backdoor - perhaps the only door - to nudge the change into full expression?

Ideas, like markets, emerge from contexts. Policies can redesign the institutional context from which ideas, and thus paradigms, arise.

Paradigms Before Policies

In Donella Meadows magnificent essay, Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a System, she writes:

“...it doesn’t matter how the tax law of a country is written. There is a shared idea in the minds of the society about what a ‘fair' distribution of the tax load is. Whatever the rules say, by fair means or foul, by complications, cheating, exemptions or deductions, by constant sniping at the rules, actual tax payments will push right up against the accepted idea of ‘fairness’…Paradigms are the sources of systems. From them, from shared social agreements about the nature of reality, come system goals and information flows, feedbacks, stocks, flows and everything else about systems.”

Paradigms are built on a bedrock of unstated assumptions. Ideas about how the world works, what’s fair, what humans are, what we might become. This paradigmatic stew of ideas form the soil from which social systems grow. The systems, then, cannot transcend the paradigm’s assumptions before transplanting into new ideological soil.

Marilynne Robinson shares this perspective when she writes in her recent essay, Is Poverty Necessary2, of her fear that a guaranteed minimum income - or basic income - might prove “undependable” given our paradigm’s indignation towards redistribution, and our associated ideas about fairness, wealth, and what people deserve:

“If there were a guaranteed minimum income, how dependable would it be, given the indignation the plutocrats express at the slightest hint that the national wealth could be distributed more equitably?”

Echoing Robinson’s concern, the economist Mariana Mazzucato cautions that arguing for a more progressive tax system is not enough. Without recasting the stories we tell about wealth, value, and the economy, such reforms will falter:

“Plato recognized that stories form character, culture, and behavior…It is not enough to critique speculation and short-term value extraction, and to argue for a more progressive tax system that targets wealth. We must ground those critiques in a different conversation about value creation, otherwise programmes for reform will continue to have little effect and will be easily lobbied against by the so-called ‘wealth creators’...Words matter: we need a new vocabulary for policymaking.”

In many cases, they’re correct: progressive policy reform follows the reform of our paradigmatic substrate of ideas. However, there are times when the reverse may be true. I’d like to explore Robinson’s example of a basic income as one such case, where perhaps the most effective strategy for cultivating a paradigm that values the end of poverty above plutocratic indignation is to begin with policy. Perhaps the policy of basic income is precisely what creates the conditions for a new paradigm to emerge.

Suggesting a policy to precede a paradigm poses serious risks. As Mazzucato points out, the policy may simply be squashed by the immune response of the prevailing paradigm. And it is bizarre to imagine democratically enacting a policy without a broadly receptive paradigm in place. But we can look to the American civil rights movement as an example of a time when just such a phenomenon occurred.

Policies Before Paradigms

The desegregation laws passed in the 1960’s promised the same conflict with existing paradigm attitudes as Robinson fears basic income does today. Despite the surges of indignation desegregation promised to incite, its policies were passed anyway. Should we have waited until racism was effectively absent - a silent minority - before desegregating schools, libraries, and employment? If so, we could still be waiting.

In this case, desegregation policies were legislated into a culture between paradigms. Unraveling institutional racism was too important to wait until the general population would accept desegregation policies without factions of contempt. Here, policy preceded its paradigm. Despite paradigmatic conflict, policies were set in place intending to embed racial equality into the design of the social system, creating a more favorable environment for a paradigm of racial equality to unfold.

In light of these two approaches - changing paradigms to beckon policies, or enacting policies to beckon new paradigms - how should we approach basic income and the elimination of poverty? Should the indignation Robinson fears keep us from considering basic income, or is the elimination of poverty urgent enough to merit a civil rights style implementation of policy in a culture between paradigms?

Economics is itself undergoing a paradigm shift from neoclassical understandings of the economy as an equilibrium system comprised of rational, self-interested agents, to a budding view of the economy as a dynamic, complex system comprised of irrational, competitive and cooperative humans. The new language and insights of complexity economics can help explore the question of basic income, and how we might approach the elimination of poverty.

Complexity Economics

Viewing the economy as a complex system radically alters how we approach economic policy, and specifically, how we design for particular outcomes. In complex systems, outcomes are opaque to forecasters. Complex systems give rise to emergent properties that cannot be predicted from knowledge of the system’s constituent parts.

Thus, working on complex systems is largely an outcome-blind process. This sullies the idea of designing for economic growth that will lead to the eventual elimination of poverty. How can we design outcome-blind policy that hopes to achieve a particular outcome? It’s a contradiction.

In Design Unbound: Designing for Emergence in a White Water World, a handbook for designing and problem solving in the context of complex systems, the authors write:

“Making progress on complex problems...requires thinking and designing with an understanding that one cannot design for absolute outcomes. The future cannot be designed…Therefore, although not solvable in any traditional sense, complex problems can be worked on by affecting the way the complex system - the context - around the problem evolves."

When confronted with an imperative as urgent as unraveling institutional racism, or obviating poverty, designing for these outcomes to arise as emergent properties of the system is a shot in the dark. But in complex systems, there is a more direct approach to achieve particular objectives, like desegregation or the absence of poverty: design them into the context of the system as conditions that reshape the evolutionary environment.

Implementing new conditions in a complex system operates on at least two levels. First, there is an immediate change to the nature of the system. Passing basic income would immediately end poverty. Civil rights laws immediately desegregated public spaces. This is like installing a perimeter fence to contain a bursting garden. Secondly, the system then grows in response to these new conditions. The garden interweaves with the fence, ivy grows through its chain links. The fence becomes a part of the garden’s structure, and plants grow symbiotically with the structure, in ways they wouldn’t have without it (upwards, along the fence).

When faced with a design imperative - a particular outcome we’d like to achieve - complexity teaches us to design them into the system as conditions, rather than try to achieve them by predicting outcomes. Rather than cutting all the plants that transgress the area of the garden, build a constraint. You cannot suppress growth of a complex system so much as redirect it.

If we conclude, with Robinson, that poverty is not necessary, then hoping for the end of poverty to emerge as an outcome of the complex economic system (by means of growth) is a game of dice. Rather, implementing a policy like basic income is to install a condition that both immediately achieves its purpose, and alters the evolutionary trajectory of the system. The emergent paradigm alters course, recreates itself symbiotically with the new conditions.

Shifting Stories

But there is a threshold of paradigmatic support required by any policy for it to pass the democratic process and become legislation. This is good; we don’t want just anybody’s idea of a desirable condition to be forced upon the system. As a policy idea approaches the threshold for potential implementation, an indispensable process of public debate ensues.

In 2019, basic income is now perched upon this hot seat, facing a series of critiques. While some concerns are reactionary, immune responses from a fading neoliberal paradigm, others are instructive, insightful, and compelling.

Taken together, these critiques of basic income ask a simple question: what is the point of basic income, and is basic income the best means for achieving it?

Notably, progressive critiques of UBI agree with Robinson: poverty is not necessary. Its end is achievable through redistributive programs that directly and immediately eliminate poverty - they just disagree on which programs to pursue, whether basic income, basic services, or universal job guarantees.

The question for the broader movement these factions comprise - how to eliminate poverty - is presently of paradigm change. How do we nudge the evolving paradigm beyond the point where implementing policy becomes feasible? On this question, let’s return to Donella Meadows:

"So how do you change paradigms? … In a nutshell, you keep pointing at the anomalies and failures in the old paradigm, you keep coming yourself, and loudly and with assurance from the new one, you insert people with the new paradigm in places of public visibility and power. You don’t waste time with reactionaries; rather you work with active change agents and with the vast middle ground of people who are open-minded.”

You find the spaces in which the paradigm shift is already underway, and amplify. Importantly, this paradigm shift is already happening. Neoclassical economics is fading into complexity economics. Neoliberalism is ceding to a vibrant, though undisciplined enthusiasm for social democracy (a movement suffering from lack of a better term than ‘social democracy’). The false distinction between free markets and government regulation is giving way to a more dynamic view of markets as outcomes that emerge from social, cultural, and political conditions. Growth is being reimagined as a mechanism for funding public goods and social property alongside private property and personal income.

A 29 year old US congresswoman - Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez - submitted the most radical piece of legislation since Roosevelt’s New Deal, a ‘Green’ New Deal, to the Senate. The deal was endorsed by two leading democratic presidential candidates. At the highest level of UK politics, the Labour party is exploring a broad spectrum of radical economic ideas, from basic income to “fully automated luxury communism”. David Graeber comments: “…it would be unwise to ignore the possibility that something historic is afoot.”

Oxford economist Kate Raworth is pursuing Mazzucato’s call for new memetic substructures to undergird new policymaking from an unusual, pictorial angle. In the same fashion that Mazzucato tells us new stories precede new policies, Raworth writes that images precede ideas. Seeing, as media theorist John Berger wrote, comes before words.

“At the heart of mainstream economic thinking is a handful of diagrams that have wordlessly but powerfully framed the way we are taught to understand the economic world…They deeply frame the way we think about economics…If we want to write a new economic story, we must draw new pictures that leave the old ones lying in the pages of last century’s textbooks.”

Raworth’s contribution is disarmingly familiar. She transforms the popular visual model of economics from a linear graph of growth, into a circular doughnut:

Elsewhere, the historian Rutger Bregman, whose 2014 book Utopia for Realists was influential in reviving interest for basic income, believes the paradigmatic obstacles to radical structural reform go as deep as the stories we tell about human nature. Accordingly, his next book promises to recast these stories we tell about ourselves in a light that tills the ideological soil for social democratic policies in the vein of basic income.

Marilynne Robinson shares Bregman’s view of our opinions on human nature as the leverage point that guides what’s next. The neoliberal capitalist world-system is built upon a particular theory of human nature. For the past 50 years, the system flourished, and so, too, did its theory that humans are selfish, rational, and competitive creatures.

“And if we have a high opinion of human nature, we will look forward to a great expansion of individual and collective creativity, a profound or exuberant pursuit of happiness that will finally begin to give full meaning to that most American phrase…We have, however, learned cynical, or, worse, banal and vapid, assessments of what we are, and they threaten us. They dull us to our circumstance, which is astonishing by any measure, and which the generations will transform again and again.”

The past 50 years of neoliberal growth - characterized by privatization and trickle-down economics - furnished the conditions that molded this cynicism, banality, and vapidity. As Douglas Rushkoff yells from his podcast, neoliberalism is a dehumanizing evolutionary context. We’re evolving to serve the very machines that were meant to serve us.

I think Bregman and Mazzucato are correct: new stories will help ground new ideas and policies. But what herculean heave of storytelling might overturn such deeply rooted ideas about human nature? Opinions are stubborn, and rarely intellectual in origin. Ideas are more often the stories we tell - rationalizations - to justify whatever worldview our accumulated emotional experiences produce. Like Raworth’s emphasis on images, emotions, too, come before words. Words and ideas layer upon, and explicate their underlying emotional substratum.

Offering people competing ideas operates only on the intellectual level, leaving the experiential, emotional substratum undisturbed. More compelling would be for people to have experiences that counter the neoliberal story of human nature. Designing for these experiences means dampening the incentives and imperatives that aggravate our fearful instincts for survival, and amplifying those conditions in which wider interests and cooperation thrive.

What more powerful condition is there to design for in this context than eliminating poverty? What does more to incite fear, anxiety, and selfishness than survival insecurity? What does more to unleash creative, cooperative ventures than having enough resources to learn, experiment, and explore?

The enduring question, then, is not whether poverty is necessary - it isn’t. Nor is it how long it might take to end poverty - it’s achievable now. The question is now one of debating the best translation of the end of poverty into the the language of system conditions. Whatever policy we use to implement the condition will guide the emergence of a new paradigm, and inaugurate a new spectrum of 21st century possibilities.

Voids & Visions

Depending on the policies used and the ideological context of those policies, designing for the end of poverty can either serve to patch the existing system, or pivot our socioeconomic trajectory onto a new evolutionary track.

For Robinson, Mazzucato, Meadows, and Bregman, the aim is singular: the end of poverty should be used as a final nail in neoliberalism’s coffin, burying neoclassical economics and narrow views of human nature along with it. Poverty is a symptom of deeper structural inequalities; its end is only an entryway into a deeper uprooting of the great deep tree trunks of assumptions that anchor the status quo.

Robinson commented that the generations will transform our assessments of human nature and possibility. This is where we find ourselves in the early 21st century: a generational turning point that will transform our assessments of what we are, and what we might become. The policies and contextualizing attitudes that we implement in this moment will guide our evolution.

The present is always seeding the future, but especially at this juncture, the conditions we design will mold what new paradigm arises to fill the void left by neoliberalism.

Teetering on this brink of paradigm turn-over, with sufficient paradigmatic change already underway, the window is open for new policies that will reshape the evolutionary conditions that sculpt the paradigm to come. This window is a design opportunity that will fertilize change in proportion to the vision we bring to it. Now is not, as Daniel Zamora writes, a time to think small.

“The power of ‘big ideas’ is that they do not aim to simply redistribute some cards, but to profoundly alter the rules of the game. ‘A revolutionary moment in the world’s history,’ [Sir William] Beveridge noted, is ‘a time for revolutions, not for patching.’”

Footnotes

- Since asexual reproduction preceded sexual reproduction, technically speaking, organisms preceded eggs. As for chickens specifically, this is probably a semantic question depending on how we define chickens and when, exactly, the organism we choose to call a “chicken” evolved. Since there was a “first chicken”, then there was an egg that preceded that particular chicken, laid by an organism that we wouldn’t consider a chicken, according to the given definition of a chicken. So organisms came before eggs, but eggs came before chickens…?

- Robinson’s essay is behind Harpers’ paywall, but I have a pdf copy. If interested in reading, just shoot me an email and I’ll send you the file.

Thanks to Kasey Klimes for comments & feedback.